- School District of Beloit

- Culturally Responsive Practices

Culturally Responsive Practices (Wisconsin Model)

-

The Urgency for Change

Despite good intentions and efforts of individual educators and school systems across Wisconsin, broad K-12 achievement gaps exist. Indeed, the gaps between our white students and our students of color are among the worst in the nation; what’s more, these gaps have persisted for over a decade (NAEP, 2015).Our nearly 50,000 English Learners, over 100,000 students with disabilities, a quarter of a million students of color, and greater than 350,000 students receiving free and reduced lunch (Wisconsin DPI, 2015) deserve equitable outcomes. And the time for us to act is now. The Model to Inform Culturally Responsive Practices describes the beliefs, knowledge, and practices Wisconsin educators, schools, and districts need to reach and teach diverse students within their culturally responsive multi-level systems of support. It’s not a checklist or a toolkit; rather, cultural responsiveness is a way of being and knowing. It’s how we show up to do the work of schools.

About the Model

About the Model

Becoming culturally responsive is a lifelong journey, not a final destination. This journey involves intentionally choosing to stay engaged in introspection, embracing alternative truths, and ensuring that every student is successful (Singleton & Linton, 2006; Promoting Excellence for All, 2015).

This process is represented on the outer circle of the model as:

WILL: The desire to lead and a commitment to achieving equitable outcomes for all students,

FILL: Gaining cultural knowledge about ourselves and others, and

SKILL: Applying knowledge and leading the change, skillfully putting beliefs and learning into action.

The arrows illustrate the ongoing, unfinished nature of this work.The Eight Areas in the Inner Circle

The eight areas in the inner circle describe actions of cultural responsiveness within WILL, FILL, and SKILL. For those just beginning this work, these areas can be used as steps in an “inside-out” process, starting with knowing oneself first, learning about others next, and then moving to action (Cross, et. al, 1989). Those further along in their journey see these areas as recursive as they purposely seek out ways to deepen their beliefs, knowledge, practice, and impact over time.

-

Become Self-Aware

Knowing how our culture has shaped who we are and where we fit in society is the first step toward understanding the profound impact of our values and assumptions on the students we serve (Center for Great Public Schools, 2008). Self-awareness impacts and is a critical consideration for every other aspect of this model.

Becoming self-aware means that individuals recognize that we bring our race and culture to every teaching and learning interaction and relationship. Here, we openly examine the way that our own culture shapes what we value, what we assume to be “right” or “wrong”, and how we act on those values and assumptions. As schools have historically reflected the norms of the dominant culture, those of us of the dominant race or culture need to work especially hard to examine power, privilege, and bias, to see the invisible (1). -

Examine the Systems Impact

School discussions about disproportionality and achievement gaps often focus on the good intentions we have and the hard work we’ve expended to serve all students. While commendable, will and effort alone are not enough. This step asks school systems to willingly examine the real effect of “the way we do things here” on our students and families, to juxtapose our student outcomes with our stated mission, vision, and values.

Disaggregating achievement data, calculating risk ratios, using root cause analyses, recognizing disproportionate representation in AP courses or Special Education, or identifying who is and isn’t present at PTO events are all examples of ways schools begin this work. These disproportionality markers are symptoms, revealing underlying cultural mismatches present in the school.

Furthermore, school equity research has shown a tendency for teams to interpret disproportionality data through a dominant racial and cultural lens. To counter this effect, culturally responsive teams seek out and include the perspectives of those most affected by disparities in outcomes in their data-based decision-making (The Equity Project, 2015). -

Believe All Students Will Learn

Each of us carries with us a lifetime exposure to societal biases about ability and potential based on gender, race, ethnicity, social class, disability status, and English language proficiency along with other characteristics and labels. These assumptions, unexamined, create barriers to providing historically marginalized students full access to high expectations, authentic connections with educators and the school environment, and rigorous coursework (Zion & Kozleski, 2005). With this step, we own up to our implicit biases and other hidden barriers to success in our classrooms and schools (Promoting Excellence for All, 2015). We recognize when we are vulnerable to acting unconsciously on stereotypes, then make the conscious choice to change our course of action: to “not let our first thought be our last thought” (Hollie, 2012).

Our unqualified school-wide commitment to teach and reach all students shows up in our vision, values, language, and practices. We don’t wait for student groups to reach a minimum cell size to pay attention. We recognize our responsibility to reach and teach each child, even and especially the “few” or “the only.”

-

Understand We All Have Unique Identities & Worldviews

We recognize that students and families are not merely products of their culture (Banks, et al, 2001). In this FILL step, we use cultural precepts as frames of reference, not as stereotypes or predictors of what individual students and families know, do, or believe. Each of us is a complex and “dynamic blend” of cultures and roles with vastly individual differences (Zion & Kozleski, 2005; Banks, et al, 2001). As such, we focus on the students and families we serve, learning about and supporting their unique strengths and blend of identities (Van Der Valk, 2016).

-

Know the Communities

This FILL action calls on us to improve our understanding of the behaviors, beliefs, values, and historical experiences of our local community, and to understand how the community perceives school. In particular, we move beyond the view of the community as a monolithic “single story” (Adichie, 2009). We recognize that the historical experiences and interactions of family and community members with school and within the community vary considerably, particularly for those whose race or culture has been historically marginalized by schools. We build knowledge, trust, and respect across the community through active listening, purposeful visits, and authentic partnerships with families and local organizations (Promoting Excellence for All, 2015).

In this FILL step, we also recognize and identify the assets in our community. We draw on the valuable wisdom from the community to positively impact our relationships with students and families; we use our local partnerships to connect students and families to supportive community resources. -

Lead, Model, and Advocate for Equity Practices

WILL and FILL alone will not change long-standing disproportionality in our schools and classrooms; we must act. This SKILL step calls on us to be courageous leaders in this work, assuming personal responsibility for catalyzing equitable conditions and outcomes for students. Equity leaders “…confront, disappoint, and dismantle and at the same time energize, inspire, and empower” (Parks, 2005, p. 210); in other words, they stand up to inequities, while simultaneously inviting others into collective learning (Larson, et al, 2016). Equity leaders also understand that lasting systems change requires directed attention at multiple levels: personal, inter-cultural group, and institutional (Potapchuk, 2004).

Equity leaders learn, do, and become. The model “…integrity, advocacy, conviction, and transparency to redress systemic inequities for diverse students, families, and communities” (Larson, et al, 2016). They skillfully draw from a range of relational, emotional, and analytical approaches to navigate a paradoxical range of demands. They follow through on commitments and have strategies to persist through predictable resistance and challenge to disrupting the status quo (Larson, et al, 2016).

-

Accept Institutional Responsibility

This SKILL step compels us as a school system to recognize that our historical policies and practices have benefitted some of our students at the expense of others (Banks, et al, 2011). We acknowledge our own practices and beliefs as the leverage points for change. We commit to adapting our school to the diversity of our students, not expecting our students or families to abandon who they are in order to be successful. We build the capacity of staff to use cultural knowledge in their day-to-day interactions with students and families and operate by the mantra that each of us is responsible for all students (Lindsey, et. al, 2003; Davis, 2007; Promoting Excellence for All, 2015). Our commitment to equity shows up in a congruence of attitudes, structures, policies, and practices throughout the school and district (Cross et al, 1989; DTAN, 2015).

-

Use Practices and Curriculum that Respects Students' Cultures

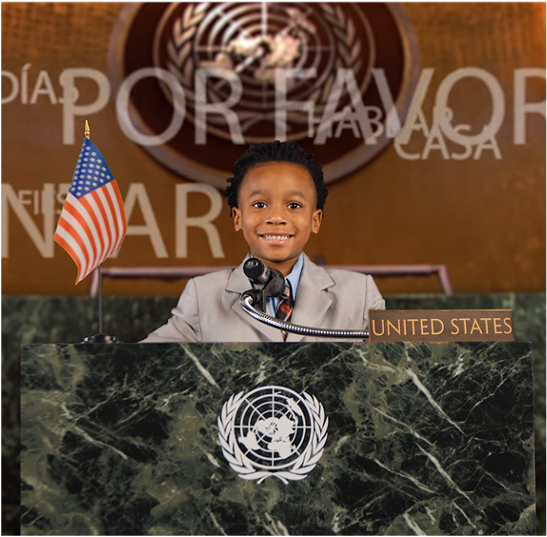

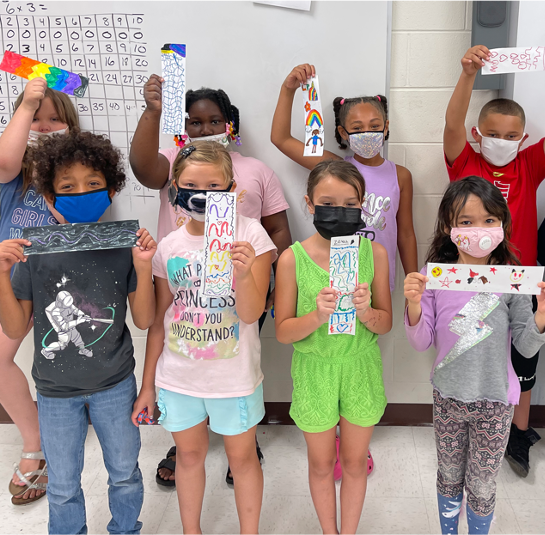

This SKILL step shows up every day for our students across the school system. Culturally responsive schools purposely image the walls, halls, and curricular materials so that each of our students sees themselves, and their future selves, as positive, belonging and valued. All-day and every day, culturally proficient educators go beyond a Heroes and Holidays approach to cultural differences, drawing from a deep and sophisticated understanding of race and culture (Murrell, N.D.). They confidently use a range of inclusive teaching strategies and ways of assessing learning that go beyond the traditional (Promoting Excellence for All, 2015).

According to Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings (1994), culturally responsive teaching “empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using culture to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes” (p 17). Thus, staff validates and affirms students’ home culture, drawing on student experience to build and bridge to rigorous educational standards. They help students become critically conscious and knowledgeable about their own cultures (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Teachers and schools build inclusive learning environments where students feel safe to express their identities and learn to relate respectfully to students whose race or culture differs from their own (Hollie, 2012, Great Lakes Equity Center, 2015).

-

Why Engage in This Work?

Schooling without culturally responsive practices diminishes the abilities of diverse students, limiting their potential for success (Banks et al, 2001; Castro, 2010). By contrast, educators and school systems embracing this work benefit from the richness that diversity brings to teaching and learning. Students and families experience school as a welcoming place, where differences and identities are both understood and valued (Center for Great Public Schools, 2008). Finally, cultural responsiveness taps into perhaps the most underutilized asset of our schools: our students, our families, and ourselves. School systems that have led this work, expanded their ways of knowing, and built their repertoire of skills have achieved both excellent and equitable results (Chenowith, 2007; Ferguson, et al, 2008; Promoting Excellence for All, 2015). It’s time for all Wisconsin schools to join in on this journey, ensuring the success of all of the students we serve.

References